Inside the desert scam factory: A young Syrian's harrowing tale

By bellecarter // 2025-02-04

Tweet

Share

Copy

- Beard, a 21-year-old Syrian refugee, fled to Dubai seeking safety but ended up trapped in a sophisticated transnational scamming operation. Desperate for work, he responded to a Telegram job ad that promised a "copy-paste role," only to discover it was a front for a cryptocurrency scam.

- Beard was coerced into impersonating "Annie," a fictional 28-year-old hotel manager, to lure victims into a fraudulent cryptocurrency scheme. The operation was highly organized, with scripts, lifestyle photos and strict guidelines to avoid suspicion.

- Beard was acutely aware of the victims' plight, referring to them as "victims" rather than "customers." Despite the normalization of the job, he felt deep guilt and deliberately sabotaged the operation by warning victims and reaching out to scam busters.

- After a tense standoff with his employers, Beard left the scam center. He found a new job in customer service. Still, the pay was significantly lower than what he earned in the scam operation, highlighting the economic desperation that often drives individuals into such roles.

- Beard's story underscores the urgent need for greater awareness and action to combat transnational scamming. In response, news.com.au has launched the "People Before Profit" campaign, advocating for legislation similar to the U.K.'s, which mandates compensation for scam victims within five business days.

The human cost of scamming

Beard was acutely aware of the human cost of his actions. "Those are not customers. Those are victims," he emphasized. "It just gets normal after a while." Despite the normalization nature of the job, Beard felt a deep sense of guilt. "You’d definitely feel bad for what you’re doing. But at the same time, it’s them or you," he said. The victims, often lonely and vulnerable, were easy targets. Beard would engage with them, building a rapport and gaining their trust. He would then subtly extract information about their financial situation to determine if they were worth pursuing. If a victim expressed doubts, the scammers had a contingency plan: a video call with the woman whose photos were being used. This woman, half Turkish and half Ukrainian, would briefly speak to the victim, assuaging their fears before moving on to the next call. Beard, however, was determined not to become a part of the scam. He deliberately sabotaged the operation by warning victims about the risks of the cryptocurrency scheme. He also reached out to scam buster Jim Browning, sending him videos and photos from inside the scam center. After a tense standoff with his employers, Beard managed to convince them to let him go, claiming he needed to return home to his family. A few months later, the scam center mysteriously went dark. Beard, now free, found a job in customer service, but the pay was a fraction of what he earned in the scam operation. "The joke is that these scams gave me an incentive to work for them because they gave me accommodation," he said. "If someone came here and actually got a job and it’s this horrible, then they’d be incentivized to go work there." In response to the rising tide of scams, News.com.au has launched the "People Before Profit" campaign, urging the Australian federal government to follow the U.K.'s lead. Last October, the U.K. introduced groundbreaking legislation mandating compensation for scam victims within five business days, except in cases of gross negligence. Head over Corruption.news for more stories about scam operations. Watch the video below that talks about dating apps for conservatives. This video is from the High Hopes channel on Brighteon.com.More related stories:

Unholy deception: AI robots clone voices of bishops to SCAM convents in Spain. Online safety: How to avoid common internet scams. New study DESTROYS SSRI antidepressant scam.Sources include:

News.com.au 1 News.com.au 2 Brighteon.comTweet

Share

Copy

Tagged Under:

scam corruption evil twisted cyber war conspiracy crime Syrian deception insanity humanitarian exploitation trafficking obey dubai enslaved cryptocurrency scam demonic times People Before Profit

You Might Also Like

Trump demands full disclosure on assassination attempts, citing withheld information

By Belle Carter // Share

The world’s worst financial catastrophe could happen soon

By News Editors // Share

Baltic Sea tensions: Is Ukraine plotting a NATO-Russia showdown?

By Willow Tohi // Share

Mother shares heartbreaking story of teen’s grisly death after the jab and Remdesivir…

By News Editors // Share

Tennessee pastor’s call for violence against Elon Musk sparks outrage

By Cassie B. // Share

Recent News

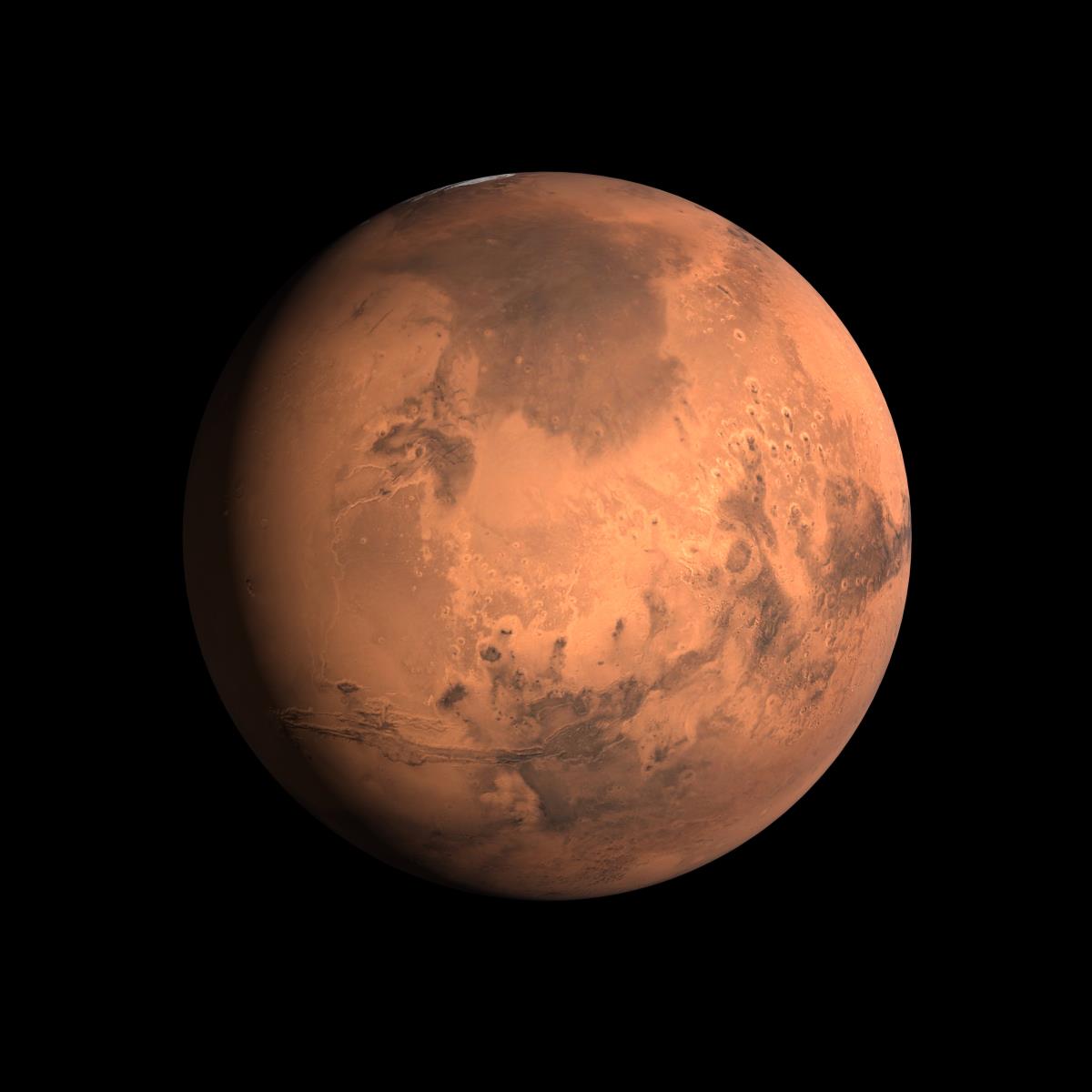

Earth-like soil patterns on Mars reveal clues to the planet’s climate history

By willowt // Share

Virologist who endorsed HCQ for COVID-19 appointed to top pandemic post at HHS

By ramontomeydw // Share