Damaged muscles in ALS patients release proteins linked to Alzheimer’s, challenging the validity of diagnostic tests

By ljdevon // 2025-03-12

Tweet

Share

Copy

A groundbreaking study has revealed that proteins long considered exclusive markers of Alzheimer’s disease are also released by damaged muscle tissue in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). This discovery, published in Nature Communications, challenges the specificity of blood tests designed to detect Alzheimer’s and opens new avenues for diagnosing ALS, a disease currently lacking definitive biomarkers.

The research, led by a team of European scientists, found elevated levels of phosphorylated tau proteins—p-tau 181 and p-tau 217—in the blood and muscle tissue of ALS patients. These proteins, previously thought to originate solely from brain pathology in Alzheimer’s, were unexpectedly traced to degenerating muscle fibers in ALS patients. The findings suggest that blood tests for Alzheimer’s may need reinterpretation, as elevated tau levels could indicate muscle disorders rather than brain disease.

Alzheimer’s or ALS? A diagnostic dilemma

The study analyzed blood samples from 152 ALS patients, 111 Alzheimer’s patients, and 99 controls across four European research centers. Both ALS and Alzheimer’s patients showed significantly higher levels of p-tau 181 and p-tau 217 compared to controls. However, while Alzheimer’s patients had higher levels of p-tau 217, ALS patients exhibited elevated p-tau 181 levels that correlated strongly with markers of muscle damage, such as troponin T. “The assumption that these blood markers only originate from the brain is being challenged,” said Professor Markus Otto, senior author of the study and director at University Medicine Halle. “Our findings limit the potential of p-tau biomarkers as screening tests because of the overlap in biomarker concentrations between AD and ALS patients.” To confirm the source of these proteins, the team examined muscle biopsies from ALS patients using immunohistochemistry and mass spectrometry. They found high concentrations of p-tau 181 and p-tau 217 in atrophied muscle fibers, providing direct evidence that muscle degeneration contributes to elevated tau levels in the blood.From hope to caution: Implications for Alzheimer’s testing

The discovery complicates the interpretation of blood tests for Alzheimer’s, which have been hailed as a breakthrough for early detection. Recent advancements in blood-based biomarkers, particularly p-tau 181 and p-tau 217, have raised hopes for minimally invasive and cost-effective screening tools. However, the study suggests that these tests may not be as specific as once believed. “Our study confirms that both blood tests for the early detection of AD are not as disease-specific as previously thought,” said Dr. Saed Abu-Rumeileh, first author of the study and a senior physician at University Medicine Halle. “A positive p-tau test could prompt physicians to perform additional diagnostic investigations, such as neuropsychological tests or imaging.” The findings also highlight the need for caution in interpreting results, especially in populations with conditions that involve muscle degeneration. For example, intense exercise or other neuromuscular diseases could potentially elevate tau levels, leading to false positives in Alzheimer’s screening.A new frontier for ALS diagnosis

While the study raises questions about Alzheimer’s diagnostics, it also offers hope for ALS patients. Currently, ALS is diagnosed through clinical examination and electromyography (EMG) testing, with no definitive blood-based biomarkers available. The discovery that phosphorylated tau proteins are released by damaged muscle tissue could pave the way for new diagnostic tools and methods to monitor disease progression. “P-tau 181 and 217 might be potential biomarkers that could be suitable for early diagnosis of ALS or for monitoring disease progression and the effectiveness of new drugs,” said Dr. Abu-Rumeileh. “What at first glance looks like a setback for Alzheimer’s disease diagnostic assessment could help us understand and maybe improve the treatment of ALS and other muscle disorders.” The study also found that longer disease duration in ALS patients correlated with higher tau levels, suggesting these proteins could serve as indicators of disease advancement. This could be particularly valuable in clinical trials, where tracking disease progression is critical for evaluating new treatments.What’s next for tau research?

The findings open new avenues for research into tau proteins, not just in Alzheimer’s and ALS but potentially in other muscle-related conditions. The study’s authors emphasize the need for further investigation to determine whether other tissues or diseases could influence tau levels and to develop more specific diagnostic tools. “Other tissues and diseases, in particular neuromuscular diseases, could also influence the p-tau levels,” noted Professor Otto. “These findings raise questions about the current theories of how tau pathology develops in AD patients and will keep scientists looking for answers in the near future.” The timing of this research is particularly relevant given the recent approval of new antibody therapies for Alzheimer’s in the U.S. and their anticipated approval in Europe. Early and accurate diagnosis is crucial for the success of these treatments, underscoring the importance of refining diagnostic tools. For ALS patients, the findings offer a glimmer of hope, as scientists and medical researchers get one step closer to realizing the similar molecular and environmental causes behind these diseases. While the disease remains incurable, earlier and more accurate diagnosis could improve access to care and participation in clinical trials, potentially accelerating the development of effective treatments. This study is a reminder that scientific progress often comes with unexpected twists. What began as a quest to refine Alzheimer’s diagnostics has uncovered a potential breakthrough for ALS, while simultaneously complicating the interpretation of Alzheimer’s blood tests. As the medical community adjusts their diagnostic approach with these findings, one thing is clear: the interplay between brain and muscle, once thought to be distinct, is far more intricate than previously imagined. This revelation not only reshapes our understanding of neurodegenerative diseases but also highlights the importance of interdisciplinary research in unlocking the mysteries of the human body. Further research should explore the underlying causes behind these diseases and changes to tau levels. Sources include: StudyFinds.org Nature.com StudyFinds.orgTweet

Share

Copy

Tagged Under:

dementia research Alzheimer's ALS blood tests Censored Science badhealth muscle degeneration antibody therapies disease progression diagnostic failures tau levels diagnostic tools neuromuscular diseases undelrying causes

You Might Also Like

FLORIDA AHCA REPORT: Illegals cost state $659.9 million in uncompensated health care

By Laura Harris // Share

USDA continues MASS CULLING of poultry to address bird flu despite criticism

By Ava Grace // Share

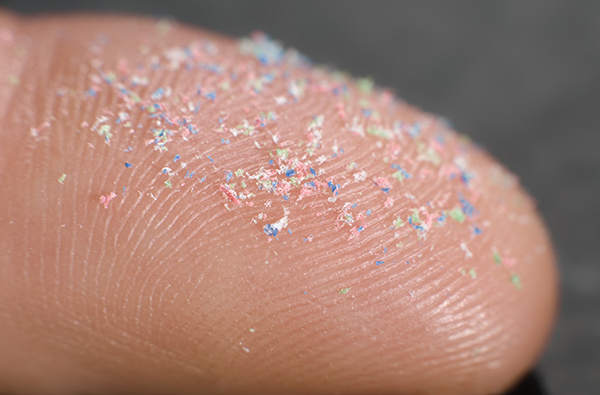

MICROPLASTICS in wastewater fuel antibiotic resistance, study warns

By Ava Grace // Share

Autism and pregnancy: What science says about risk factors

By Olivia Cook // Share

PLANDEMIC BLESSING: For those who survived, the PLANDEMIC was a blessing in disguise

By S.D. Wells // Share

Recent News

Reporter faces backlash for warning illegal immigrants of ICE raids

By lauraharris // Share

EU to ban privacy cryptocurrencies and anonymous accounts by 2027 under new AML rules

By lauraharris // Share